|

| From

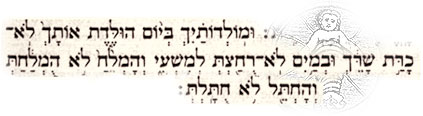

ancient times, salt was used both to indicate and to repel the presence

of evil. This is evident in the ritual of mothers salting their

babies mentioned in the book of Ezekiel, a practice which included

but was not limited to Hebrew women: "Your father was an Emorite

and your mother a Hittite, and as for your birth, on the day you

were born your navel was not cut nor were you washed in water for

cleansing, you were not salted at all nor were you swaddled...."[1] |

Bible

and comparative religion scholar Theodor Gaster writes that the salting

of newborn babies was common practice among Jews (TB Shabbat

129b), early Christians and Greeks in the early centuries of the Common

Era: In later centuries, this practice appears among other peoples as

well: "The Arabs protect their children by placing salt in their

hands on the eve of the seventh day after birth; the following morning

the midwife or some other woman strews it about the house, crying, 'Salt

in every envious eye.' …In standard Catholic ritual, salt is applied

to the lips in baptism to exorcise the Devil, and in medieval Sweden

it was then put under the infant's tongue. The Germans did the same

thing immediately after the child had been delivered and salt was also

placed near the child to ward off demons. In the Balkans and among the

Todas of Southern India, newborn children are immediately salted; while

Laotian and Thai women wash with salt after childbirth to immunize themselves

from demonic assault. In the northern counties of England, it is customary

to tuck a small bag of salt into a baby's clothing on its first outing."[2]

The practice of salting babies is still current in the Orient.

As for your birth, when you were born your navel cord was

not cut, and you were not bathed in water to smooth you; you

were not rubbed with salt, nor were you swaddled. (Ezekiel

16:4)

|

|

Salt being incorruptible, averts demons and protects

against black magic. As an ancient writer put it, witches and

warlocks "like their master, the Devil, abhor salt as the

emblem of immorality."

* * *

If one found his road blocked by highwaymen, he

should hurriedly grasp a handful of salt or earth, whisper an

incantation over it, and fling it in the direction of his attackers,

rendering them powerless to harm him. [2]

|

The potency of salt as an anti-demonic object, is evident in other beliefs

and practices common to medieval European peoples. It was believed that

salt is never found at the Witches' Sabbath feast, and the Inquisitor

and his assistants at a witch-trial were warned to wear bags containing

consecrated salt for protection against the accused.

According

to medieval Jewish authorities, salt must be set on a table before

a meal is begun "because it protects one against Satan's denunciations."

As the Kabbalists saw a connection between the mathematical value of

three times the name of God (YHVH) and that of

the word "salt," they taught that if one dipped his bread

three times into salt when reciting the benediction, and if one ate

salt after each meal, he would

be protected against harm. For this reason, salt was used in many rites

connected with birth, marriage and death, as well as in medicine.

Writes

Joshua Trachtenberg; "Very often salt and bread were jointly prescribed

to defeat the strategems of spirits and magicians. When a witch assaults

a man, he can bring about her death by forcing her to give him some

of her bread and salt. Murderers ate bread and salt immediately after

their crime to prevent the return of their victim's spirits to wreak

vengeance upon them…. The common practice of bringing salt and

bread into a new home before moving in, usually explained as symbolic

of the hope that food may never be lacking there, was probably also

in origin a means of securing the house against the spirits."[3]

|

[1]

Ezekiel 16:4[back]

[2]

Theodore

Gaster, Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament (New

York: Harper & Row, 1969; republished by Peter Smith, 1990)

[back] [2]

Theodore

Gaster, Myth, Legend, and Custom in the Old Testament (New

York: Harper & Row, 1969; republished by Peter Smith, 1990)

[back]

[3]

Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study

in Folk Religion. © copyright 1939 Behrman's Jewish Book House,

Inc. (published by Atheneum and reprinted by arrangement with

the Jewish Publications Society of America), p. 160.[back]

|

|

|

|

|